I believe this course was a valuable learning experience for me. It made me reconsider what childhood means and what it has meant in the past. It has done the same for how I think of education. We were given the opportunity to look at how these subjects were approached in the past which allows us to consider how it is approached now, and how they may be approached in the future. We learned about how much education was valued in the past and how that has changed over time. We also learned about how the experience of childhood and education has differed between generations and between ethnicities. The class discussions also allowed us to consider the opinions of others and hear how they understand a topic. I think the discussions are particularly valuable even if we disagree with what is being said, as long as we are open-minded about what we are hearing and learning.

Author: Darla

On Finding Sources

Most of the sources I used during my research were books. In order to have a better understanding of the residential school experience and to be able to write about it, I had to gather sources that included Survivors talking about their time their or somehow reflecting on what they experienced. What I found was that most of these testimonies were published in books and not in journal articles. The journal articles I found were mostly studies focused on how residential schools affected later generations. Unfortunately, the books I found were generally not about specific schools, provinces, or time periods, which made it difficult to do research about a certain province or decade. I can say with some certainty that most of the testimonies I read were from people who attended a residential school in the 1930s or later. Also, because the classroom experience was often a small chapter of each book, I ended up using quite a few sources to gather enough information to write my research paper. Overall, it was not difficult to find sources, but it was difficult to ignore some that I knew would be interesting but irrelevant to what I wanted to write about.

On Choosing a Topic

When I think about the research that I have done during my time in university, I realize that much of it focuses on Indigenous issues. Whenever I was given the opportunity to choose a topic, I gravitated towards ones about First Nations people. For this course on childhood and education, it seemed a natural choice to write about residential schools. What I did not realize was how difficult it would be. It was difficult not only because of the subject matter but because it was hard to narrow the topic down. The schools ran for over one hundred years, with the last school closing in 1996. Once I thought I had my topic narrowed down, I kept reading. I was looking for sources that would help me answer the questions I had. What I found after reading through a few chapters from several different books was that I would not find many testimonies from Survivors that had good classroom experiences at residential school and also received good grades. The children who were sent or taken to residential school did not speak English when they arrived, which meant that most of their time spent there would be about learning the language and unlearning their first language. I had to find a new approach to this topic and it was becoming clear that the majority of Survivors did poorly at these schools, which was by no means their own fault. They had to learn a new language and endured severe punishment when they made a mistake in class or spoke their Native language in or out of the classroom. Instead of writing about academic success in residential school, I decided to write about the residential school experience and how some Survivors succeeded after residential school.

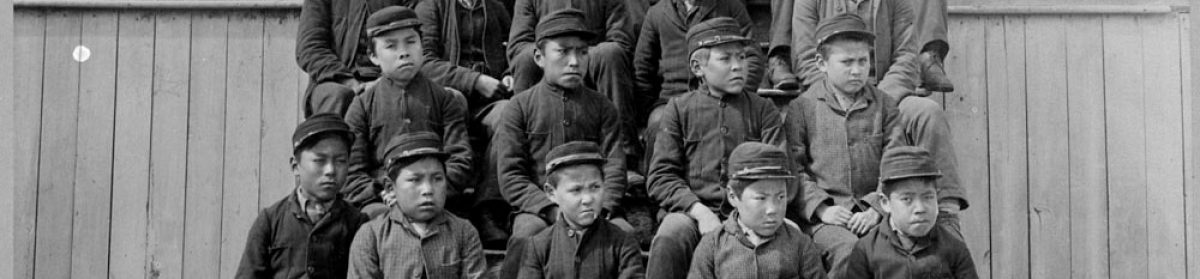

[Students attending the Metlakatla Indian Residential School, British Columbia, date unknown.]

Reminder From a Survivor

One of the difficult things about doing research is that you often come across great material that doesn’t always make it into the final paper. This is a quote I thought was worth sharing, whether or not it makes it into the research paper:

“As Survivors, we ride waves of vulnerability for a lifetime and for generations. We were subjected to real risk factors including hunger, loneliness, ridicule, physical and sexual abuse, untimely and unseemly death. As we struggle to throw off the shackles of colonization we lean heavily toward healing and resilience becomes our best friend.”[1]

Most people know that residential schools were a horrible, abusive experience for many who attended but it usually seems overlooked that the Survivors and the generations that follow them are resilient. This quote is a reminder of everything that was endured and also that the Survivors pushed forward.

[1] Madeleine Dion Stout, “A Survivor Reflects on Resilience,” in Speaking My Truth: Reflections on Reconciliation and Residential School, (Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2012), 49-50.

Week 11

Both of the readings that I chose look at responses to changes in the school curriculum. The first, Wien and Dudley-Marling’s “Limited Vision: The Ontario Curriculum and Outcomes-Based Learning” looks at the shift from the Common Curriculum to the Ontario Curriculum. This shift was supposed to improve the learning experience, but it was actually a step backwards for teachers and the curriculum. The new Ontario Curriculum tried to move away from “Students will” as the focus of grade outcomes, which “set up an authoritarian series of commands for teachers and school boards.”[1] Instead of improving the curriculum and learning outcomes for students, the Ontario Curriculum put a different stress on teachers to use a fixed amount of time to teach content.[2] The second reading that I chose, Nancy Janovicek’s “The Community School Literally Takes Place in The Community,” looks at alternative schools in British Columbia from 1959 through the 1980’s. Instead of focusing purely on academics, these schools also taught skills that were essential for living in rural communities.[3] Part of what drove these families to create these communities and schools was the direction that public schools were going in with education. Public schools were emphasizing science, technology, and math instead of the humanities, which not everyone agreed with.[4] These rural schools, like the Argenta Friends School, “sought to develop the whole person.”[5]

The third reading that I chose is Agnes Grant’s Finding My Talk. Instead of looking directly at life in residential schools, Finding My Talk looks at the lives of women after residential school. I read the chapter on Shirley Sterling, a Nlakapamux First Nations woman from a reserve near Merritt BC. Sterling spent eleven years in Kamloops Residential School, and moved on to take grade thirteen in Kamloops.[6] The chapter goes on to describe Sterling’s life after Residential School and her academic success. A quick search on Google shows that Sterling completed her Ph.D. in 1997, and as stated in the chapter she did started university after her own children had moved out, which means she likely attended Residential School in the late 1950s and 1960s. I think her pursuit of further education and her success in doing so shows that her Residential School experience was not entirely negative. While the chapter does not go into detail, she must have done well in her classwork to finish the final high school grade and continue on to university later on in life. What I like about Finding My Talk is that it shows readers examples of life beyond Residential School.

Works Cited

Grant, Agnes. Finding My Talk: How Fourteen Native Women Reclaimed Their Lives after Residential School. Calgary: Fifth House, 2004.

Janovicek, Nancy. “‘The community school literally takes place in the community’: Alternative Education in the Back-to-the-land Movement in the West Kootenays, 1959 to 1980.” Historical Studies in Education, 24, 1 (Spring 2012): 150-169.

Wien, Carol Anne and Curt Dudley-Marling. “Limited Vision: The Ontario Curriculum and Outcomes-Based Learning.” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 400-412.

[1] Carol Anne Wien and Curt Dudley-Marling, “Limited Vision The Ontario Curriculum and Outcomes-Based Learning.” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 402.

[2] Wien and Dudley-Marling, “Limited Vision” 405.

[3] Nancy Janovicek, “’The Community School Literally Takes Place in the Community’: Alternative Education in the Back-to-the-Land Movement of the West Kootenays, 1959-1980,” 151.

[4] Janovicek, “The Community School Literally Takes Place in the Community,” 152,

[5] Janovicek, “The Community School Literally Takes Place in the Community,” 160.

[6] Agnes Grant, Finding My Talk: How Fourteen Native Women Reclaimed Their Lives after Residential School, Calgary: Fifth House, 89.

Week 10

Each of the papers I am writing about for this week’s readings were written about progressive reform in schools during the 20th century. The final word in both Amy von Heyking’s “Selling progressive Education to Albertans” and Robert M. Stamp’s “Growing Up Progressive? Part I” seems to be that the progressive curriculum failed to be properly implemented in schools. Each paper expresses generally the same ideas as to why the progressive curriculum failed in the classroom: lack of funding, lack of properly educated and trained teachers, and teachers not wanting to stop using proven teaching methods. As Stamp states, the idea of the new curriculum was to move the focus from the content to the child.[1] Stamp proceeds throughout the paper to question whether what was occurring in the classrooms was actually progressive, noting how some children were held back while others skipped grades, something that still occurred while I was in elementary and likely still occurs today. [2] The final sentence in von Heyking’s paper nicely captures what occurred in Alberta: “Whether or not the educationalists were successful in transforming schools, they did succeed in portraying themselves as the real experts in education.”[3] These educationalists tried to convince parents to support the progressive curriculum, though, like in Ontario, it did not truly transfer to changes in the classroom. Paul Axelrod expresses more of the same ideas in his paper, stating that he does not remember experiencing what was supposed to be the progressive school system in Ontario.[4] Axelrod points to the population growth that occurred between 1946 and 1961 and the need to recruit teachers for the growing enrolment that followed as one of the reasons a progressive system was not implemented in Ontario.[5] Axelrod does point out that unconventional teaching methods were being used in Toronto to meet the needs of children, which may not fit the progressive model but is a move away from the traditional.[6] Overall, it seems that the progressive curriculum was not put in to practice despite the likelihood it would have been better for students.

References

Axelrod, Paul. “Beyond the Progressive Education Debate: A Profile of Toronto Schooling in the 1950s.” Historical Studies in Education 17, no.2 (Spring 2005): 227-241.

Heyking, Amy von. “Selling Progressive Education to Albertans, 1935-1953,” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 340- 354.

Stamp, Robert M. “Growing Up Progressive? Part I: Going to Elementary School in 1940s Ontario.” Historical Studies in Education vol. 17, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 187-98.

Citations

[1] Robert M. Stamp, “Growing up Progressive? Part I: Going to Elementary School in 1940s Ontario,” Historical Studies in Education vol. 17, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 188.

[2] Stamp, “Growing up Progressive?,” 190

[3] Amy von Heyking, “Selling Progressive Education to Albertans, 1935-1953,” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (EDs.), Schooling in Transition” Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: Toronto University Press, 2012, 351.

[4] Paul Axelrod, “Beyond the Progressive Education Debate: A Profile of Toronto Schoolings in the 1950s,” Historical Studies in Education 17, no.2 (Spring 2005): 228

[5] Axelrod, “Beyond the Progressive Education Debate,” 232.

[6] Axelrod, “Beyond the Progressive Education Debate,” 232.

Week 8

This week’s readings make it clear how much power and influence those deemed “experts” in the 20th century had. They were given the ability to determine what a healthy and competent child was. While this makes sense in theory, in practice it gave doctors, psychologists and the like too much power. It should lead readers to question who we call experts and those who have authority in certain situations. Each of this week’s readings shows the influence that experts had on the general population. There was an apparent focus on establishing what was normal and then deciding what to do with those who did not fit their definition. Two of these readings also show that racism played a large role in determining who was subnormal, problematic, or unhealthy.

Each paper deals with some form of an expert and how they influenced particular populations. Gerald Thomson’s paper focuses on the work of Josephine Dauphinee, a nurse and teacher in early 20th century British Columbia. Dauphinee wanted to keep “a strong Anglo-white majority in British Columbia” and thought of “eugenic measures . . . as a means of efficient social engineering to solve the problems of the poor.”[1]She worked to spread the concept and actualization of Special Classes for subnormal children in B.C.[2] Through Dauphinee and her colleagues, we can see both racism and classism in the way they determined who was subnormal and how they were treated. Cynthia Comacchio’s paper focuses on the “youth problem” in the 20th century. What followed the Great War included many changes in society and behaviour, according to Comacchio these changes “challenged the established order of things, especially in terms of collective morality and the historic relations of authority premised on class, gender ‘race’ and age.[3] The issues in Comacchio’s paper were about sexism and dealing with issues around age. Comacchio notes that the social sciences were focused on determining what was normal in individuals and social groups, which I think is also seen in the other readings this week.[4] Mona Gleason’s paper focuses on public health in relation to race and class. Much like the subnormal children of Thomson’s paper, the concern of public health was focused on those in lower classes and those who were non-white. Gleason points out that “protecting the public ‘health’ . . . meant excluding and demonizing a particular portion of the public.[5] Much like the youth problem in Comacchio’s paper, there was a focus on the health of children by health professionals.[6] Each paper presents a group of professionals or experts attempting to determine what is best for society in some way.

References

Comacchio, Cynthia. “‘The Rising Generation’: Laying Claims to the Health of Adolescents in English Canada, 1920-70.” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 19, no.1 (2002): 139-178.

Gleason, Mona. “Race, Class, Health: School Medical Inspection and ‘Healthy’ Children in British Columbia, 1890-1930.” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 19, 1 (2002): 95-112.

Thomson, Gerald. “‘Through no fault of their own’: Josephine Dauphinee and the ‘Subnormal’ Pupils of the Vancouver School System, 1911-1941.” Historical Studies in Education 18, no.1 (Spring 2006): 51-73.

Citations

[1] Gerald Thomson, “‘Through no fault of their own’: Josephine Dauphinee and the ‘Subnormal’ Pupils of the Vancouver School System, 1911-1941,” Historical Studies in Education 18, no.1 (Spring 2006): 52, 55.

[2] Thomson, “’Through no fault of their own,’” Historical Studies in Education, 53.

[3] Cynthia Comacchio, “‘The Rising Generation’: Laying Claims to the Health of Adolescents in English Canada, 1920-70,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 19, no.1 (2002): 140.

[4] Comacchio, “’The Rising Generation,’” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 143.

[5] Mona Gleason, “Race, Class, Health: School Medical Inspection and ‘Healthy’ Children in British Columbia, 1890-1930,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 19, 1 (2002): 97

[6] Gleason, “Race, Class, Health,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 99.

Week 6

In order to decolonize education efforts should be made to properly educate students of all ages on Canada’s history of colonization and residential schools and also avoid alienating students by forcing them to change their hair, language, and other culturally related identifiers. All three of this week’s readings look at some aspect of the Aboriginal experience with residential schools in Canada. Barman’s paper focuses on finding out why residential schools failed and had such “far-reaching consequences.”[1] Barman’s paper further goes into four reasons how and why Aboriginal children were schooled for inequality and failure.[2] Helen Raptis’ paper focuses on the various factors that went into the integration or delayed integration of Aboriginal students into public schools, these reasons included both economic and apparent personal capabilities of the children.[3] Paige Raibmon’s paper is written on George Henry Raley, a residential school principal, and his impact on the school. While many former students praised the principal, he still was known to use “terms such as ‘savage,’ ‘heathen,’ and ‘weird’ to describe Native culture.”[4] These papers show how Aboriginal students were treated and othered by many of the people in authority positions.

References

Barman, Jean. “Schooled for Inequality: The Education of British Columbia Aboriginal Children.” In Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012, 255-276.

Raibmon, Paige. “’A New Understanding of Things Indian’: George Raley’s Negotiation of the Residential School Experience.” BC Studies, 110 (1996), 69-96.

Raptis, Helen. “Implementing Integrated Education for On-Reserve Aboriginal Children in British Columbia, 1951-1981.” Historical Studies in Education, 20, no. 1 (Spring 2008), 118-146.

Citations

[1] Jean Barman, “Schooled for Inequality: The Education of British Columbia Aboriginal Children,” In Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012, 256.

[2] Barman, “Schooled for Inequality,” 261.

[3] Helen Raptis, “Implementing Integrated Education for On-Reserve Aboriginal Children in British Columbia, 1951-1981,” Historical Studies in Education, 20, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 121, 124-125.

[4] Paige Raibmon, “’A New Understanding of Things Indian’: George Raley’s Negotiation of the Residential School Experience,” BC Studies, 110 (1996), 71.

Week 5

The idea of school segregation seems so distant from where we are today, but looking at this week’s readings we remember that it was not that long ago that it was common and even demanded. Each of this week’s readings display the opposition and difficulties faced by the oppressed minorities the paper focuses on. The educational oppression experienced in the 19th and 20th century is indisputable. Claudette Knight’s paper is written on the experience of those who came to West Canada to escape slavery and/or racism.[1] They, like the Chinese in Stanley’s paper and the black women in Moreau’s paper, faced a lot of resistance while trying to attend or have their children attend the public schools. In their desire to be educated and educate their children, separate schools were opened by women in their own homes to educate the children.[2] Similarly, the Chinese parents resisted the segregation being forced on the children by having them strike.[3] The Chinese community also resisted the segregation by using and promoting literacy in written Chinese.[4] The last paper, by Moreau, I found most interesting. Like Knight’s paper, it focuses on the educational oppression of black people, specifically black women. What I liked best about Moreau’s paper was that she actually conducted interviews with women who were part of the oppression.[5] These three papers share the same ideas of oppression and resistance by minorities. They knew what they wanted and they took what they believed to be the necessary steps to try and achieve their goals.

References

Knight, Claudette. “Black Parents Speak: Education in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Canada West.” in Sara Burke and Patrice Mileweski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 225-237.

Moreau, Bernice. “Black Nova Scotian Women’s Experience of Educational Violence in the Early 1900s: A Case of Colour Contusion.” Dalhousie Review 77, no. 2 (1977): 179-206.

Stanley, Timothy J.. “White Supremacy, Whinese Schooling, and School Segregation in Victoria: The Case of the Chinese Students’ Strike, 1922-1923.” in Sara Burke and Patrice Mileweski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 237-252

Citations

[1] Claudette Knight, “Black Parents Speak: Education in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Canada West,” in Sara Burke and Patrice Mileweski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 229.

[2] Knight, “Black Parents Speak,” 228.

[3] Timothy J. Stanley, “White Supremacy, Whinese Schooling, and School Segregation in Victoria: The Case of the Chinese Students’ Strike, 1922-1923,” in Sara Burke and Patrice Mileweski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 238.

[4] Stanley, “White Supremacy,” 244.

[5] Bernice Moreau, “Black Nova Scotian Women’s Experience of Educational Violence in the Early 1900s: A Case of Colour Contusion,” Dalhousie Review 77, no. 2 (1977): 182.