Sager’s paper focuses on the shift in the teaching realm from primarily male to female teachers. This feminization of teaching occurs in the later half of the nineteenth century.[1] He notes that teaching was exploitative and oppressive but could be self-affirming and empowering.[2] Sager’s paper is a speculation of why this feminization occurred during this time period, and he offers several possible explanations for it. What I found interesting in the paper was “their movement into teaching was also a movement towards material independence, intellectual self-realization, and social respectability.” [3] I find this statement contradicts what is shown in Wilson’s paper as far as the social respectability is concerned because the paper opens with a young teacher’s suicide following comments from parents in the community.[4] Wilson’s paper is really about the difficulties and dangers teachers in rural communities faced. They faced social difficulties including town gossip and no social life, as well danger from “lone prospectors passing to and fro.”[5] Sometimes a rural community was designated as a man’s school due to the living and social conditions.[6] Typically a comment such as this would upset me, but considering the isolation, danger and other difficulties of these communities at the time I find it appropriate. Both of these papers do a good job of showing what it was like for women teachers in the 19th and 20th centuries.

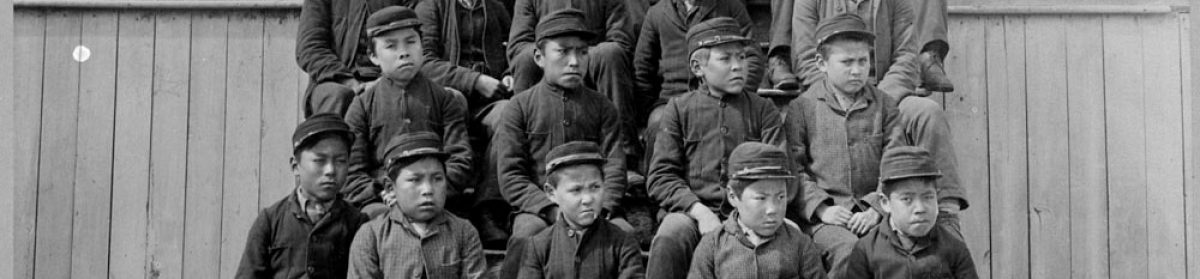

I found an interesting paper about the Coast Salish community and the challenges regarding education they faced. One elder attended two residential schools in his youth in British Columbia and a high school in Washington later on.[7] One of the residential schools that he attended was apparently “notorious for conditions of deprivation, neglect, and abuse” which is sadly unsurprising given the history of residential schools.[8] The elder noted that while he faced racism at the high school it provided “opportunities to advance his ability to take part in the social economy.”[9] This paper brought forth a comparison that I had not considered because it was a situation I had not considered and therefore provides a different perspective for secondary school after residential school for the Coast Salish people.

References

Marker, Michael. “Borders and the borderless Coast Salish: decolonising historiographies of Indigenous schooling.” History of Education, vol. 44 no. 4, 480-502.

Sager, Eric W. “Women Teachers in Canada, 1881-1901: Revisiting the ‘Feminization’ of an Occupation.” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 140-165.

Wilson, J. Donald. “’I Am Here to Help If You Need Me’: British Columbia’s Rural Teachers’ Welfare Officer 1928-1934.” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 201-222.

Citations

[1] Eric W. Sager, “Women Teachers in Canada, 1881-1901: Revisiting the ‘Feminization’ of an Occupation,” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 143.

[2] Sager, “Women Teachers in Canada,” 143.

[3] Sager. “Women Teachers in Canada,” 157.

[4] J. Donald Wilson, “’I Am Here to Help If You Need Me’: British Columbia’s Rural Teachers’ Welfare Officer 1928-1934,” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 202.

[5] Wilson, “I Am Here to Help If You Need Me,” 208, 210.

[6] Wilson, “I Am Here to Help If You Need Me,” 209.

[7] Michael Marker, “Borders and the borderless Coast Salish: decolonising historiographies of Indigenous schooling,” History of Education, vol. 44 no. 4, 480.

[8] Marker, “Borders and the borderless Coast Salish,” 480.

[9] Marker, “Borders and the borderless Coast Salish,” 480.