Most of the work that has been done on residential school have a strong focus on the negative aspects of the schools. This is understandable, given the number of horrible things that are known to have occurred at many of these schools. This paper attempts to include as many positive and negative aspects as possible to give a good idea of what happened and the impact they had on the children who attended. Unfortunately, there is no time period or provincial focus due to the work that has already been done including such a wide array of Survivors from different parts of the country who attended residential school during different times. While most if not all experienced a loss of language and culture, the experience children had with residential schools seems to have varied greatly outside of these two common elements. First I will give a brief history of the purpose of residential schools in Canada. Next, by looking at the various reasons that children attended residential schools, I hope to give an idea of what life was like as an Indigenous person in Canada. Then the paper will look at how long children tended to stay in the residential schools and what influenced the length of their stay. Following this, the paper will look directly at the classroom experience and what children were learning. Next will be how well students performed in class and speculation on how the classroom success and experience may have influenced whether students pursued further education. While much work has focused on the abuse in schools without recognizing any positive aspects, it would not be fair to Survivors to only recognize the few positives that occurred during this period of residential school. That is why I will look at abuse and violence that occurred in the classroom next, followed by abuse and violence that occurred outside of the classroom. Finally, I want to examine success after residential school by looking at Survivors who attended college, university, and further education as adults or were successful in other ways. While residential schools did not provide the students with an adequate education to succeed this did not stop all students from succeeding as adults.

Approximately 150,000 Indigenous children attended residential schools from 1867 until the last school closed in 1996.[1] The federal government became involved in mandating and funding the schools shortly after federation.[2] The goal of these schools was to assimilate Indigenous children into European culture and religious beliefs, which was referred to as “the Indian problem,” with the goal being getting rid of it.[3] Those who ran the schools wanted to remove the Indian from the child and make them more civilized from their point of view. Children could attend these schools starting at age six until age sixteen. The schools were run by religious groups, with 60% run by Catholic groups, 30% by Anglican, and the remaining 10% divided between various Protestant groups.[4]

Most people have the understanding that children were forced to attend residential schools by some outside authority. The reasons they went to these schools, like many aspects of the residential school experience, varied. Some children, like Rita Joe who spent years in foster care, may have asked to be sent to a nearby school instead of another home.[5] Other children were brought to schools by their parents. There are many reasons that may have influenced parents to do this. For Alice French and her brother, they were brought to All Saints Anglican Residential School by their father following the hospitalization of their mother.[6] Many stories likely resemble Dorothy Moore’s, she was brought to Shubenacadie Residential School by her mother without any sort of explanation.[7] Agnes Grant states that one “factor that influenced early school attendance was the devastating poverty First Nations experienced with the coming of European settlers.”[8] While Grant is referring to the first schools of the 19th century, the poverty that was experienced would have continued into the mid-20th century and continued to lead parents into sending their children to the schools. She states that “some parents reluctantly sent children to residential schools where they would at least be warm and fed.”[9] Again, this is referring to the early schools before 1930, but I believe some parents would have had the same feeling later on.

The amount of time children spent in residential schools seems to vary slightly less than other aspects of the schools. As Grant states, “a common practice was to keep students in residential schools until the mandatory age of sixteen.”[10] However, this does not mean that all children stayed until they were sixteen, or that they all spent the same amount of time at the schools since some children started later than others. Rita Joe, for example, only spent four years at residential school, from age twelve to sixteen.[11] After turning sixteen she was given a choice between staying at the school to become a nun and working at an infirmary.[12] Unless a child was removed from the school by their parents, staying until the age of sixteen was most common. Truancy was also not uncommon in the schools. “Many students ran away to escape the discipline of the school.”[13] Some students would run away from the schools only to return later on.[14] Sometimes a child would run away knowing they would not be able to make it home but simply not being able to stand residential school life anymore.[15] The total amount of time spent at the schools varies depending on when they started attending as some were sent to school as soon as they were able while others started school later.

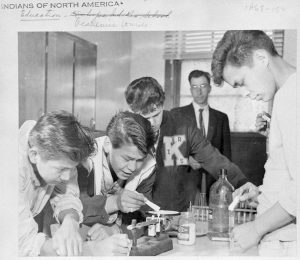

Generally, it seems a child’s time in class looked the same from school to school. Agnes Grant states that “in all cases the students were expected to learn English before any real ‘learning’ could take place.”[16] Grant also notes that it took most children two or three years to learn English but some did learn the language faster.[17] In class, reading was the main focus but there is not much information about what was actually taught to the students.[18] A half-day system was typical in the schools.[19] The other half of the day was focused on religious indoctrination and hard labour.[20] Putting the children to work was a way to offset the costs of running the schools.[21] An Albertan residential school in the 1950s provided students with a minimal education, according to one survivor.[22] Another Survivor states that in one “school, which was minimally funded . . . the children were taught prayers, basic reading skills, and syllabics.”[23] There is some evidence that suggests some schools provided higher quality education than average to their students. The photograph of students in a chemistry class at Kamloops Indian Residential School is one example.[24] I think this photograph is an example of a school that had enough funding to provide more options for students, and thus, likely could provide a better education. It appears that most schools had similar curriculums, with the exceptions being the schools that had more funding available.

Based on Survivor testimony, most students did not receive good grades while attending residential school. One Survivor, Clara Monroe, feels that the education she received at the Roman Catholic School in Alberta was very limited because there was such an emphasis on religion instead of academics.[25] Some students realized how limited their education from residential school was when they integrated into public schools.[26] The children were often given the impression that no one expected them to succeed.[27] One Survivor, Walter Jones, recalls what another student was told after asking if he would make it to grade twelve, to which he was told that his people would never get an education for professional jobs but rather work all the jobs that white people do not want.[28] The children were not encouraged by their teachers or supervisors to do well, nor were they expected to do so.

Discipline in the classroom was often exceedingly harsh or even violent. Reading through Survivors’ testimonies shows how many children witnessed or experienced the extreme discipline that was found in residential school classrooms. One Survivor recalls being threatened with missing dinner if they disobeyed.[29] Many children received severe punishment for speaking their first language instead of English. When Ida Wasacase was in residential school, she accidentally spoke Cree and the supervisor responded by hitting her over the head with a board.[30] This board had a nail in it, which had gone unnoticed by the supervisor, and the nail was driven into Ida’s head.[31] She never spoke Cree again after the incident.[32] Isabelle Whitford recalled having her supervisor pull her ears and shaking her head when she did not get the correct answer in math.[33] Another Survivor recalled a boy who could not read because he stuttered, but that did not stop the supervisors from abusing or humiliating him, which did nothing to help him.[34]

While not all children experienced abuse outside of the classroom this does not mean that it was not an issue. Some children experienced excessive discipline for what seems to have been minor misbehaviour. Sister Dorothy Moore remembered being strapped for running up the stairs when she should have walked.[35] She also recalled one Sister that was particularly cruel, the sister once covered the water fountain so the children could not get a drink.[36] The same sister also set out apples in the recreation room, then punished children for stealing when they took one.[37] Moore often felt ill while at school, and when she complained about stomach pain she was given a whole bottle of castor oil.[38] Moore also had her face pushed into her own vomit, presumably by a sister or other supervisor.[39] Madelein Dion Stout reflects “we were subjected to real risk factors including hunger, loneliness, ridicule, physical and sexual abuse, [and] untimely and unseemly death.”[40] She is recognizing, as we all should, that physical harm was not the only hurt endured by children at these schools. Each of these punishments seems excessively harsh and sometimes even cruel compared to the supposed misbehaviours that lead to them.

The poor quality of education and lack of encouragement that children received at residential schools did not stop all of them from pursuing further education or success. Many students described the education they received as limited, but some did do well in school. Rita Joe went on to become a well-known poet. One of her best-known poems is titled “I Lost My Talk.” In the interview, Rita Joe said that she felt it was her job to fix how Indigenous people were represented in literature, media, and popular culture.[41] Alice French wrote a book about her experience at residential school titled My Name is Masak which was published in 1973.[42] The Restless Nomad was written during a time in which not a lot had been published about residential schools.[43] She also wrote a sequel in which she analyzes her experienced, titled The Restless Nomad, which was published in 1992.[44] Sister Dorothy Moore went on to become a very accomplished woman after spending two years in residential school. She feels her academic learning “would have foundered as it did for so many residential school students.”[45] As discussed earlier, her short time in residential school still allowed enough time to experience harsh and unnecessary punishment. She continued her schooling after leaving residential school and attended Holy Angels High School at twenty years old, where she fought to be able to write the provincial exams.[46] She attended Teacher’s College, then in 1974 completed both Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Education degrees.[47] In 1984, Moore earned a Masters in Educational Psychology.[48] In 1989, Moore was recognized with the “Stephen Hamilton Outstanding Achievement Award in Education for her contributions and efforts in pursuing higher education for Mi’kmaq youth.”[49] These many achievements are not Moore’s only achievements, but they capture her desire to become well-educated and also to educate the generations after her. The last Survivor I will discuss is Agnes Grant, who wrote Finding My Talk, and No End of Grief, among other works. I think the achievements and success of these Survivors show that they were able to overcome the experiences they had at residential school, even if they do not view those experiences as particularly bad.

I believe the topic of residential schools and the quality of education that children received there closely relates to many topics discussed throughout the semester. Specifically, I think it relates to compulsory schooling, racialized childhoods, segregated schooling, separate childhoods and Indigenous education, and growing up Canadian. Some connections between the topics, such as racialized childhoods, segregated schooling, and Indigenous education are more obvious. Part of the creation of residential schools was the idea that Indigenous peoples were different and needed to become more the same, thus connecting the racialization of childhood to residential schools. Compulsory schooling is an interesting concept, it implies that child absolutely must attend school. However, just like the mothers in urban cities, parents really had the final say of when children started going to school and usually when they left school, as well. Segregated schooling is another more obvious point, residential schools were for Indigenous children and no Caucasian children would have been found attending these schools. Like other segregated schools in Canadian history, residential schools were set up to target a certain population and only people from that population. Indigenous education can be looked at in a few different ways, such as traditional ways of learning, residential schools, and integrated schools. Under the topic of “Growing up Canadian” we discussed what children were taught in schools in order to be a good citizen. The same can be said about residential schools in that they were trying to change Indigenous children in a way that would allow them to be viewed as good and civilized citizens.

Most children who attended residential school did not receive an adequate education nor did they have positive experiences in the classroom or outside of it. The majority of the children were forced to attend the schools in some way, either by their parents or another authority figure. The children received a limited education in the classroom that did not set them up to succeed academically later on in life. Much of the focus was on teaching the children English and the religious beliefs of the school. While some children did well in the residential schools, others did quite poorly. Based on the testimonies, it seems that most children did not receive good grades. Many Survivors talk about experiencing or witnessing physical violence in the classroom as punishment for not knowing the answer to a question or for another behaviour that was deemed bad by the supervisor. Violence and other forms of abuse were not uncommon outside of the classroom either, but like every aspect of residential schools, there are survivors who experienced the bad, only witnessed it, and did not have the common experience. Despite all of these factors, there are Survivors who went on to post-secondary education and did well. There are Survivors who have their Ph.D., who have written books or poetry and have been published, and have done well for themselves.

Bibliography

Capitaine, Brieg and Karine Vanthuyne. Power Through Testimony: Reframing Residential Schools in the Age of Reconciliation. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2017.

Chrisjohn, Roland D., Sherri L. Young, Michael Maraun. The Circle Game: shadows and substance in the Indian Residential School experience in Canada. Penticton: Theytus Books, 2006.

Feir, Donna L.. “The Intergenerational Effects of Residential Schools on Children’s Educational Experiences in Ontario and Canada’s Western Provinces.” International Indigenous Policy Journal 7, no. 3 (2016): 1-44.

Feir, Donna L.. “The long-term effects of forcible assimilation policy: The case of Indian boarding schools.” Canadian Journal of Economics 49, no. 2 (2016): 433-480.

Fox, Basil. “[Chemistry class at Kamloop Indian Residential School, British Columbia, ca. 1959.]” Photograph. Kamloops, British Columbia. From Library and Archives Canada. http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/pam_archives/index.php?fuseaction=genitem.displayEcopies&lang=eng&rec_nbr=3487979&title=Chemistry+class+at+Kamloop+Indian+Residential+School%2C+British+Columbia%2C+ca.+1959++&ecopy=a185845-v8 (accessed Nov. 3, 2017)

Grant, Agnes. Finding My Talk: how fourteen Native women reclaimed their lives after residential school. Calgary: Fifth House, 2004.

Grant, Agnes. No End of Grief: Indian Residential Schools in Canada. Winnipeg: Pemmican Pub, 1996.

Loyie, Larry, Wayne K. Spear, and Constance Brissenden. Residential Schools: With the Words and Images of Survivors. Brantford: Indigenous Education Press, 2014.

Rogers, Shelagh, Mike DeGagne, and Jonathan Dewar. Speaking My Truth: Reflections on reconciliation & residential school. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2012.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. The Survivors Speak: a report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015.

Primary Source

“[Chemistry class at Kamloop Indian Residential School, British Columbia, ca. 1959.]”

[1] Donna L. Feir, “The Intergenerational Effects of Residential Schools on Children’s Educational Experiences in Ontario and Canada’s Western Provinces,” International Indigenous Policy Journal 7 no. 3 (2016): 3.

[2] Donna L. Feir, “The long-term effects of forcible assimilation policy: The case of Indian boarding schools,” Canadian Journal of Economics 49, no. 2 (2016): 437.

[3] Roland Chrisjohn et al., The Circle Game, 61.

[4] Donna L. Feir, “The long-term effects of forcible assimilation policy: The case of Indian boarding schools,” 437.

[5] Agnes Grant, Finding My Talk: how fourteen Native women reclaimed their lives after residential school, (Calgary: Fifth House, 2004), 36.

[6] Grant, Finding My Talk, 55.

[7] Grant, Finding My Talk, 75.

[8] Grant, Finding My Talk, 21.

[9] Grant, Finding My Talk, 22.

[10] Grant, Finding My Talk, 21.

[11] Grant, Finding My Talk, 36.

[12] Grant, Finding My Talk, 42-43.

[13] The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak: a Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, (Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015), 133.

[14] The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak, 135.

[15] The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak, 135.

[16] Agnes Grant, No End of Grief: Indian Residential Schools in Canada, (Winnipeg: Pemmican Pub, 1996), 165.

[17] Grant, No End of Grief, 165.

[18] Grant, No End of Grief, 167.

[19] Larry Loyie et. al. Residential Schools: With the Words and Images of Survivors, (Brantford: Indigenous Education Press, 2014), 45.

[20] Roland Chrisjohn et all. The Circle Game: shadows and substance in the Indian Residential School Experience in Canada, (Penticton: Theytus Books, 2006), 93.

[21] Chrisjohn et all. The Circle Game, 93.

[22] The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak, 123.

[23] Brieg Capitaine and Karine Vanthuyne, Power Through Testimony: Reframing Residential Schools in the Age of Reconciliation, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2017), 164.

[24] Basil Fox, “[Chemistry class at Kamloop Indian Residential School, British Columbia, ca. 1959.]” Photograph. Kamloops, British Columbia. From Library and Archives Canada. http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/pam_archives/index.php?fuseaction=genitem.displayEcopies&lang=eng&rec_nbr=3487979&title=Chemistry+class+at+Kamloop+Indian+Residential+School%2C+British+Columbia%2C+ca.+1959++&ecopy=a185845-v8

[25] The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak, 122.

[26] The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak, 123.

[27] Ibid,.

[28] Ibid,.

[29] Capitaine and Vanthuyne, Power Through Testimony, 165.

[30] Agnes Grant, Finding My Talk, 25-26.

[31] Grant, Finding My Talk, 25-26.

[32] Ibid.,

[33] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak, 121.

[34] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak, 122.

[35] Agnes Grant, Finding My Talk, 76.

[36] Grant, Finding My Talk, 76.

[37] Ibid.,

[38] Ibid.,

[39] Ibid.,

[40] Shelagh Rogers, Mike DeGagne, and Johnathan Dewar, Speaking My Truth: Reflection on Reconciliation & Residential School, (Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2012), 49.

[41] Agnes Grant, Finding My Talk, 37.

[42] Agnes Grant, Finding My Talk, 51.

[43] Grant, Finding My Talk, 51.

[44] Grant, Finding My Talk, 52.

[45] Grant, Finding My Talk, 77.

[46] Grant, Finding My Talk, 80.

[47] Grant, Finding My Talk, 80.

[48] Grant, Finding My Talk, 81.

[49] Grant, Finding My Talk, 83.