Christopher Clubine’s paper “Motherhood and Public Schooling in Victorian Toronto” is focussed on truancy in the late 19th century. Clubine states that “it was thought that urban families relied solely on wages earned by the father” which reminded me of John Bullen’s paper from the week two readings.[1] It seems to have been a common misconception that urban families could afford to have their children attend school full-time. I found it interesting that mother’s were really the ones in charge of deciding whether the children attended school and until what age they attended.[2]

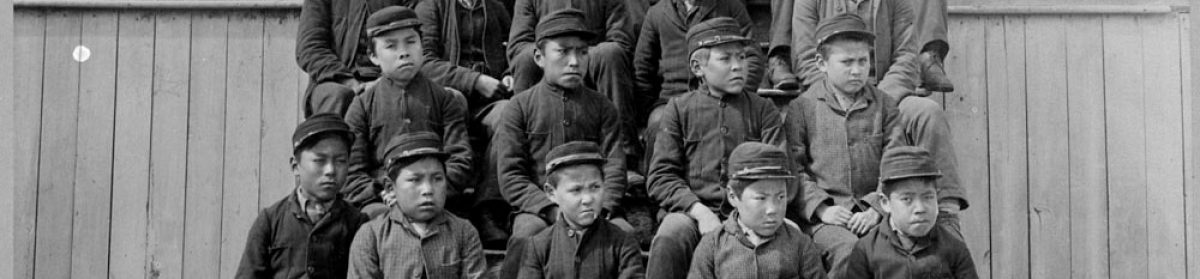

Robert McIntosh’s paper “The Boys in the Nova Scotian Coal Mines: 1873-1923” notes that a boy was generally considered to be under 18, though in the mines it was those between ages 8 and 21.[3] Death and disability due to mining accidents were not uncommon among boys.[4] During this time period, more regulation was gradually put in place to protect the boys, though they were a valuable asset to have in the mines due to their smaller size and lower wages.[5] Over time it seems to have been decided that the boys should be protected from mining accidents and instead be receiving a formal education.

For my research, I am interested in looking at comparing the education received by residential school attendees and indigenous non-attendees. This week I found a study, “The Intergenerational Effects of Residential Schools on Children’s Educational Experiences in Ontario and Canada’s Western Provinces.” Feir states that “many authors suggest that Aboriginal youths’ current educational struggles are part of the intergenerational fall-out from residential schools.[6] She also looks to the 2006 census, noting that the graduation rate for First Nations was only 50% while it was 90% for non-First Nations, which suggests that there may be a correlation between having a family member that attended residential school versus those who have no history of residential school attendance.[7] While I appreciate the information Feir provides, I think it may be too recent to fit what I am looking for, but I will look into the sources she used for more information.

References

Clubine, Christopher. “Motherhood and Public Schooling in Victorian Toronto.” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Educations, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 115-126.

Feir, Donna L. “The Intergenerational Effects of Residential Schools on Children’s Educational Experiences in Ontario and Canada’s Western Provinces.” The International Indigenous Policies Journal, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2016: 1-46.

McIntosh, Robert. “The Boys in the Nova Scotian Coal Mines: 1873-1923,” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press: 126-139.

Citations

[1] Christopher Clubine, “Motherhood and Public Schooling in Victorian Toronto,” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Educations, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012: 117.

[2] Clubine, “Motherhood and Public Schooling,” 120.

[3] Robert McIntosh, “The Boys in the Nova Scotian Coal Mines: 1873-1923,” in Sara Burke and Patrice Milewski (Eds.), Schooling in Transition: Readings in the Canadian History of Education, Toronto: University of Toronto Press: 126-127.

[4] McIntosh, “The Boys in the Nova Scotian Coal Mines,” 127.

[5] McIntosh, 127.

[6] Donna L. Feir, “The Intergenerational Effects of Residential Schools on Children’s Educational Experiences in Ontario and Canada’s Western Provinces,” The International Indigenous Policies Journal, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2016: 1.

[7] Donna L. Feir, “The Intergenerational Effects of Residential Schools,” 1.