This week’s readings make it clear how much power and influence those deemed “experts” in the 20th century had. They were given the ability to determine what a healthy and competent child was. While this makes sense in theory, in practice it gave doctors, psychologists and the like too much power. It should lead readers to question who we call experts and those who have authority in certain situations. Each of this week’s readings shows the influence that experts had on the general population. There was an apparent focus on establishing what was normal and then deciding what to do with those who did not fit their definition. Two of these readings also show that racism played a large role in determining who was subnormal, problematic, or unhealthy.

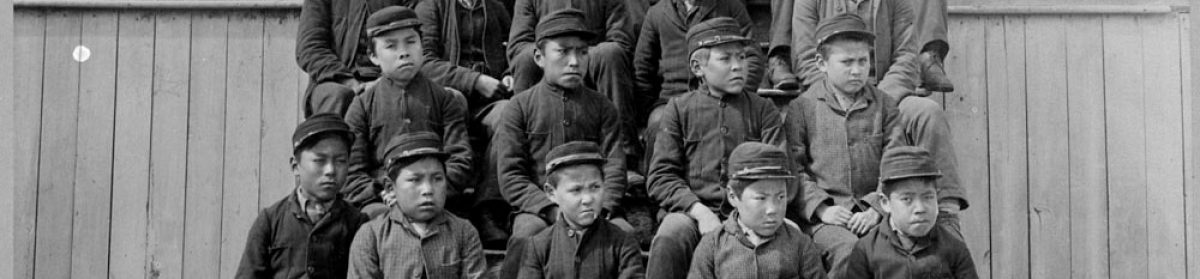

Each paper deals with some form of an expert and how they influenced particular populations. Gerald Thomson’s paper focuses on the work of Josephine Dauphinee, a nurse and teacher in early 20th century British Columbia. Dauphinee wanted to keep “a strong Anglo-white majority in British Columbia” and thought of “eugenic measures . . . as a means of efficient social engineering to solve the problems of the poor.”[1]She worked to spread the concept and actualization of Special Classes for subnormal children in B.C.[2] Through Dauphinee and her colleagues, we can see both racism and classism in the way they determined who was subnormal and how they were treated. Cynthia Comacchio’s paper focuses on the “youth problem” in the 20th century. What followed the Great War included many changes in society and behaviour, according to Comacchio these changes “challenged the established order of things, especially in terms of collective morality and the historic relations of authority premised on class, gender ‘race’ and age.[3] The issues in Comacchio’s paper were about sexism and dealing with issues around age. Comacchio notes that the social sciences were focused on determining what was normal in individuals and social groups, which I think is also seen in the other readings this week.[4] Mona Gleason’s paper focuses on public health in relation to race and class. Much like the subnormal children of Thomson’s paper, the concern of public health was focused on those in lower classes and those who were non-white. Gleason points out that “protecting the public ‘health’ . . . meant excluding and demonizing a particular portion of the public.[5] Much like the youth problem in Comacchio’s paper, there was a focus on the health of children by health professionals.[6] Each paper presents a group of professionals or experts attempting to determine what is best for society in some way.

References

Comacchio, Cynthia. “‘The Rising Generation’: Laying Claims to the Health of Adolescents in English Canada, 1920-70.” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 19, no.1 (2002): 139-178.

Gleason, Mona. “Race, Class, Health: School Medical Inspection and ‘Healthy’ Children in British Columbia, 1890-1930.” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 19, 1 (2002): 95-112.

Thomson, Gerald. “‘Through no fault of their own’: Josephine Dauphinee and the ‘Subnormal’ Pupils of the Vancouver School System, 1911-1941.” Historical Studies in Education 18, no.1 (Spring 2006): 51-73.

Citations

[1] Gerald Thomson, “‘Through no fault of their own’: Josephine Dauphinee and the ‘Subnormal’ Pupils of the Vancouver School System, 1911-1941,” Historical Studies in Education 18, no.1 (Spring 2006): 52, 55.

[2] Thomson, “’Through no fault of their own,’” Historical Studies in Education, 53.

[3] Cynthia Comacchio, “‘The Rising Generation’: Laying Claims to the Health of Adolescents in English Canada, 1920-70,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 19, no.1 (2002): 140.

[4] Comacchio, “’The Rising Generation,’” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 143.

[5] Mona Gleason, “Race, Class, Health: School Medical Inspection and ‘Healthy’ Children in British Columbia, 1890-1930,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 19, 1 (2002): 97

[6] Gleason, “Race, Class, Health,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 99.